Claudia Hart : Halfway Between Real And Unreal

This wide-ranging conversation took place at Wallplay Gallery in Manhattan, January 2018, during the installation of Claudia’s multimedia mixed-reality solo show Flower Matrix, co-presented with Transfer Gallery.

The interview was originally published in edited form as Halfway Between Real And Unreal: Claudia Hart in BOMB Magazine’s online edition, which can be viewed here.

Claudia Hart. Portrait by Stephen Spera.

Sean Capone: Just to set the scene: we're here for the new version of the installation The Flower Matrix. Give us a quick break down of the viewing experience.

Claudia Hart: The idea of Flower Matrix is to create a lounge for viewing Virtual Reality. What that means is you experience the immersive experience of VR in which you walk into a simulated environment and feel, phenomenally, that you're in it. I was interested in bringing that a step closer to the real world. What's interesting about the simulation technologies that I use as opposed to traditional ‘flipbook’ animation -- because I don't think of what I do is animation but more like simulation -- is that the experience of 3D environments is a phenomenal experience, a trompe l’oeil experience. When you build both a physical environment for viewing it and a virtual environment, you feel like you're in a realm halfway between real and unreal. You've entered this ‘gateway zone’, a kind of fantasy, imaginative or Heaven-like dream space, and in that space you build things, and you set physical processes and allow them take on physical properties as real objects do in the real world, and then live their own lives. This is a totally different relationship in terms of regular animation, which is more of a subject-object relationship. In other words, the subject is the maker who makes an object, which is a drawing ... and then another and another, and the flipbook is a thing.

SC: But with 3D animation, you’re not really drawing things either, you use automated processes to give the appearance of space and movement. Isn’t that already a rupture from traditional animation?

CH: I think it's something else entirely depending on what you emphasize. I don't consider myself a ‘character animator’ but I do work with digital bodies. I work with physics. I'm not actually interested – I reject out of hand, actually – the old fashioned animation strategies of tweening and creating ‘good’ animation. What's amazing to me is creating automatons – giving them life to go and do things on their own. So I set up physics environments in which the bodies are acted upon by forces. There's very little traditional animation involved. I mix simulations technologies with motion capture. I capture motion data with sensors attached to real bodies, and submit those to physical simulations. It's closer to making robots than to making a flipbook.

SC: In a way you’re still an “animator” but one that skips the history of cinematic animation -- to go back to the original sense, the alchemical concept of animating or simulating life: Frankenstein, the golem, the homunculus, that kind of thing.

Claudia: Exactly. And I think you could trace the history back to the 18th century automatons and early robotics. All of these things I was fascinated by before I did 3D.

SC: Fairytales and mythology informed a lot of your early work. The first piece I saw of yours was Ophelia -- a single shot of a 3D rendered nude woman, suspended lifeless, floating underwater.

CH: Well, I started working about 35 years ago, so I was an ‘intermedia artist’. I would create characters and environments, and worked in a variety of media to create props or artifacts. I was involved with tropes from Romanticism and the 19th century. Ophelia was done with 3D and simulation, but I'm talking about work that I did with Pat Hearn Gallery when I was in my twenties. I was creating environments, like sets, in which characters have been ... and I’d put in, like, fake photographic images of them. I didn't tell a literary, narrative story but you could take these clues and put them together. I never wanted to be an animator but when I fell upon simulations technology, it was like discovering a genie in a bottle. I could do the whole thing inside a simulated space. See, I was actually a kid whose mother was a left-wing intellectual, so I wasn’t allowed to watch television. Cartoons were totally forbidden. So I never looked at anything like that and I still find them sort of horrifying. My early work was inspired by all the Romantic poets. I went from reading texts inspired by Rousseau, Lord Byron and Frankenstein in my early shows, from that directly into simulations. So I don't feel any connection to the traditions of animation, whatsoever.

SC: You're coming from more of a performative or theatrical aspect. You're not confined to just screen based work. You use projections, performances, scenography, costume enhancement using AR (augmented reality)...

CH: First I’d like to explain what I mean by simulations, or ‘Simulism’. In one of my classes we had the same discussion. I'm not part of the animation thing, I don't want to teach cartoon walk cycles; the students I have don't want to do that either. In my class I asked “What do you think we do? Animation? No!” So we came up with the word ‘Simulism’, which sort of nails it, because it sounds like Impressionism, or Futurism.

SC: <laughs> Art history needs some new -isms!

CH: I know! The idea of simulations technology is that you're dealing with an interface, which is a liminal environment. When you use it you feel like the interface is an actual gateway for the XYZ-coordinate, theatrical space that you can look into. Using optics, physics, and anatomy, you give the virtual environment physical qualities and material qualities, you set up a camera and lights and it looks like a doll's house or a Sims world. You create a world where you set up conditions, set up lights, and shoot it with your little camera. Using a touch screen or a mouse, in a short time you feel like you're in there, you feel your body is in this architectural space. Sixteen hours go by, sitting motionless and you haven’t moved, but you think you’ve been moving! You're in a halfway zone between the real and the unreal, your body thinks it’s real -- a liminal space. You become a cinematographer for this simulated theater; you shoot it, then you ‘render’ all these frames -- another alchemical process, like rendering fat -- and that becomes a movie. The whole process is alchemy, and the relationship to ‘drawing’ and ‘flatness’ is null. And just to clarify, to use these 3D simulation tools, they’re very difficult to operate, the most complicated software ever made – so we are computer engineers to a large extent. And, within that, these complicated softwares, you enact. You go through the interface, a gateway, and enter the XYZ theatrical simulated space...your body thinks you’re in there, and then you enact things, using interfaces that all use the language of different sciences: optics, anatomy, the physics of materials, gravity.

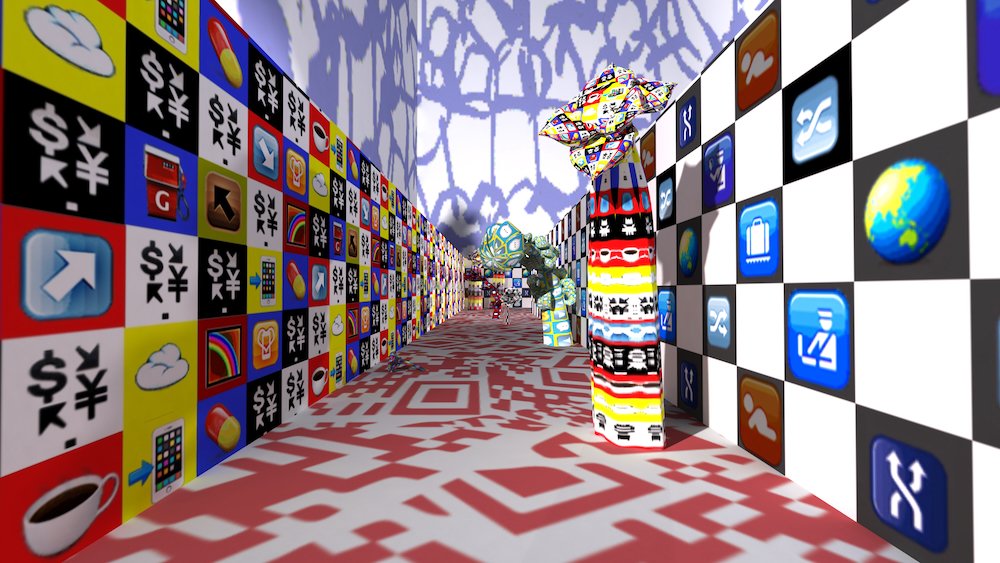

Installation view of Flower Matrix, Wallplay Gallery, NYC.

SC: You break through the fourth wall, like a theater proscenium. Which describes the experience of the work, but what of its real-world affect? Once you zoom out again.

CH: We should talk about the psychological and perceptual effects in culture, that have been made possible by these scientific visualization tools – which were originally used for flight simulation, for simulating illness, or creating buildings, and so on, and are now being used to make games and movies. We have this stuff that looks like real photography but is almost totally fake… it’s simulated. This creates another idea about what might be real or what is not-real … these are very profound questions that have come up totally with our current President, with the last election, all the crises happening in internet communications … questions enabled by these digital filmmaking technologies, about what is truth and what is not-truth.

SC: So your proposition is that these visualization technologies have contributed to the crisis of truth and ‘consensual reality’ in our country? I remember this used to be a serious discussion in new media theory: that seamless digital fakery would begin to impact our perception of the news, and falsified visual evidence would become a commonplace kind of propaganda. I don’t think this has happened that blatantly, where fake items are being collaged into footage. But it’s happened more insidiously ... and tactically on social media, as we’ve seen – where there is no stable framework for ‘reality’ as far as our information is concerned.

CH: Right, but I think it's not just about image culture, it's about institutions. What we are experiencing is fascinating, where traditional institutions are breaking down. So from my point of view as a woman -- or your point of view as a gay man -- it’s like, hallelujah! We’re happy about that, right?

SC: There was always the liberatory aspect of it, right? We wanted to demolish the idea of dominant, consensual reality.

CH: Yes. We're experiencing a moment of technological explosion, of advancement due to digital technology in which we can simulate for futures. These were used originally to simulate futures: flight simulation, weather models, organ transplants. Experimental, quantum physics says “what you imagine is real.” These are scientific, theoretical ideas about the shifting of the ‘real’, and at the same time we're experiencing the breakdown of institutions. So, people are anxious about the crisis of what’s real, and what we’ve experienced with Trump and how he took the election by manipulating truth and the news. This isn’t just about changing images, but creating pseudo infrastructures, fake institutions, “fake news” … he uses the term negatively but he created it.

SC: So what can we do? How do we take control of the simulation again, and use it for liberation, as artists or filmmakers? Because these tools are in our hands too, and we’re really good at using them.

CH: I think we do use it for liberatory purposes. I think we saw it with the far right, how they use it to foment hate, suspicion, racism, and mischief in a creepy way.

SC: Do you think they got it from us? As artists, were we just playing with it, as a conceptual theoretical thing – but they saw the potential of it, and weaponized the mischief?

CH: In an interview with Patrick Lichty, we talked about the Dadaists and detournement, as institutional critique. Artists used that as a strategy, now we see the actual playing out of that in a culture that has become largely nihilistic. I think we can once again use it to build something, create something liberating and affirming. To build bridges and relationships. I’ve noticed with young artists now, is kind of a neo-hippy thing. Young artists who I know work with these technologies – maybe they’re just my gang of kids – and are making constructive visionary work with it.

“These are very profound questions that have come up with our current President, with the last election, all the crises happening in internet communications … questions enabled by these digital filmmaking technologies, about what is truth and what is not-truth.”

SC: I wanted to talk about the kind of visual evolution that I've seen in your work over the last decade. You've actually moved away from 3D-rendered verisimilitude and more into a flat videogame visual space, with flat lighting and strobing tile grid patterns as a signature motif. Wouldn’t photorealism be a way of pulling people into that trompe l’oeil space of simulism convincingly?

CH: I rejected the verisimilitude. What I'm doing is I'm trying to hypnotize people. I actually think I do. I've developed techniques for putting people into trance states. We just asked that question, “what can we do?” I want to bring people into meditative, transitory states and have out-of-body experiences. You know you're in an artificial space. Over the years, working with physics simulations and real world conditions, what I noticed is if I did certain things and used certain slippages off the actual ‘real’ – real physics and real optics – if I introduced irregularities and randomness in those mathematical algorithms, I could make people pass out or go into a trance state.

SC: You knocked people out?

CH: I would knock myself out! In my piece Optic Nude, which was based on a historical ‘pornographic’ photograph, I started covering everything with patterns, I added strobing lights, sounds of monks chanting and put it on a cloth simulation blowing in the wind. I take different kinds of algorithmic natural patterns, then I offset them, like fairy dust, I add a little bit of chaos and irrationality … and, you pass out! When I made it I was suffering from a tremendously bad period of insomnia. I’d watch it and I’d fall asleep, so I knew I was on to something. During my show at Transfer Gallery, where I showed the Doll’s House work, I was approached by a young man, a mathematician, who had just written his PhD on generating randomness, and he felt convinced that I had achieved this in a kind of irrational, physical bodily way. And then, during the MFA program I teach at SAIC, a woman – a doctor in neuroscience – asked me if I knew that what I made induces hypnosis. I said yes, that’s why I do it. So all that happened as a result of my desire to simulate the real.

SC: A more direct, perceptual intervention, rather than letting people stand outside the frame, peering into the simulated space.

CH: You actually enter the space -- I make them into an animated character. Right? I take their bodies and digitize them. I bring them in.

SC: Oh god, you’re the Master Control Panel from TRON. <laughs>

CH: TRON was where I entered, where I got interested. When I first got involved with 3D animation I was friends with the original TRON team. I shared my studio with Michael Ferraro who was on the original crew and developed an early rendering light simulation program. And the TRON people were originally with the Department of Defense… the original simulators.

SC: I’m connecting your idea of ‘meditative space’ to why you don’t consider yourself an animator. You seem engaged in a kind of ‘de-animating’. With your earlier work you talked about “video objects” and using 3D to portray the compressed time and space of a painting -- figures in nature where nothing is happening, or happening so slowly to the point of inertness.

CH: I started as an object maker. I would do these performative environments where I would appear in images as a character. What happened over the 20-plus years I've been doing this is that I, as a maker, went through the liminal gate and experienced this bodily phenomena, of thinking I was a vaporized automaton – I was a TRON character. That was the ‘art act’ – an act way more profound and meaningful to our time than the traditional subject/object thing, where you just look at the art object. You become the animated character, you physically experience it.

The Flower Matrix, VR view.

SC: Can you talk about your ongoing project, The Real-Fake?

CH: In 2010, Rachel Clarke came up to me at a CAA panel and wanted to learn more about 3D, and asked if I wanted to work on a project together. So we started the research and looking for others, we found about ten people or so. Rachel teaches at Cal State Sacramento and they gave us the opportunity to do a show and make a catalog. Instead of doing a show, we decided to do a website, with the fantasy that it would go viral and others could use it to teach with, so we posted a series of essays and hosted a conference at the university. We made it a kind of manifesto, but we were formally trying to define the qualities of the ‘real-fakeness’, which we're now calling simulism. We came up with different categories, put it online and toured the show. In 2016 we did another version based on requests from conversations on Facebook. Whereas before we had ten participants we could barely find, this time we had at least sixty people, and these were just the people I knew personally.

We realized several things. The press release talked about things like ‘truth’ and ‘news’; the show opened one week after the election. All the things we talked about had happened. We used the language “Real-Fake News”, which was a creepy embodiment of what was happening. That discussion became profoundly relevant. There was this idea that we were creating sites of transformation, with the artists that we chose.

SC: There's one question in the back of my head. How is this work, our work, any different than what artists and poets and philosophers have been doing for centuries? The idea that art or theater can depict an alternate reality? Is it different now simply because it's no longer notional? Meaning, I can sit down and make something that looks just as good as something from Pixar or CNN. There’s no ‘Plato’s Cave’ metaphor in effect…

CH: I think the Plato's Cave idea was washed out by the position of the avant-garde. The avant-garde was about deconstruction and institutional critique, emerging from around the time of World War One, with the disillusionment people had with government, and progress itself …. the Enlightenment notion of progress was beginning to break down. The epoch that followed, now we are in a nihilistic, crisis moment. I think that what we do is emerging from the conceptual art tradition, the structuralist strategies of making that emerge from conceptual art. We deconstruct and reconstruct, we do deep readings of structures, and use them to build this alternative reality – the idea of art as a site for transformation, contemplation, and the spiritual (although I hate that word) – for profound human issues of Being. I don’t even know if my work is “critical”, I don’t think of it as pedagogy.

SC: I’ve been using the word “mythology” a lot more lately than I ever would before. But it sounds like you’re getting into more metaphysical territory.

CH: But, what is “metaphysics”?

SC: Well, I guess I’m thinking of...I’m nervous about the kind of reactionary mysticism of the ‘60s. The whole ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’ rejection mentality … and, like we’re seeing now, with Jaron Lanier’s rejection of the initial precepts of virtual reality and social media, there’s no liberatory potential in these technologies. He’s saying we need to radically unplug from the Matrix.

CH: Well, to talk about my piece which is up here, The Flower Matrix, this piece is a metaphor for the interweb but it’s also about ‘casino capitalism’. It's like going into a casino. I lived a chunk of my life when I was a kid in Reno and Lake Tahoe…

SC: Wow, I had no idea! This is so important to understanding the look of your work. A casino is also a weird kind of liminal, over-sensorial environment you enter into and disconnect from the outside world.

CH: I lived in a lot of places like that when I was a kid. What I did was: I took the icons and emojis and computer symbols for power, money and addiction, as many as I could find. And I made these strobing flickering algorithmic patterns, and created a labyrinth out of Greek mythology, the labyrinth of the Minotaur. I went onto Google Warehouse and found a model of the labyrinth someone had built, covered it with my patterns and brought it into a virtual environment. In this one, there's only one entrance. A couple people have made it out... most don't. It’s pretty big. I made five species of flowers and I covered them with the strobing patterns for power and addiction. It’s sort of a nightmare of consumption, but also of Heaven. It's a topsy turvy ‘Alice’ world, and actually, if you do make it out you get enveloped in a deep fog and popped back to the beginning. You can never get out.

SC: Like in old video games. You go out the right side and come back in the left. The labyrinth with its shiny treasures and endless repetition, is basically Pac-Man. I’m thinking now, in your work, there’s actually a recurring theme of imprisonment: the Princess dresses, the statuesque bodies which seem petrified ... and a casino is also a captive environment.

CH: I think it has something to do with dying, or transcending the constraints of the body. <long pause> It also has to do with the fact that I have parathyroid disease. My body doesn’t produce calcium, potassium, magnesium… I have glass bones. As I’ve aged, I’m getting twisted. I have arthritis, and I am in pain a lot. I do a lot of body practice. So I think a lot of this work’s about the prison of the body, how you transcend the limits of the body.

SC: Early conversations about VR would always fall back on that old trope, the Cartesian mind/body split. How we can upload ourselves out of these bodies, away from these troublesome meat sacks...

CH: If you’re gonna think about the Cartesian split with more depth, you might say that the mind is the conscious mind, and the body is the unconscious mind. There is a difference but there's no one without the other. The body is the mind. What you are talking about is dealing with the grotesque, which is what your work’s about. You can look at my early work which is dealing with the grotesque, but I was more interested in the decorative.

SC: It took me a long time to find my way into using the body in a performative way, getting away from the decorative. But when I saw your Ophelia piece, and the Seasons character work, I understood right away what you were doing. You were creating work about bodies dissolving into nature and patterns. Which took me back to my original inspirations, like Ovid's Metamorphoses.

CH: I think I'm just making contemporary versions of that, rather than referencing [those myths]. A young documentary filmmaker, she compared my work to Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, even though he’s still referencing historical mythologies. What I think I'm trying to do is create these fairy-tale worlds that are dark and have the unconscious, the aspirations ... the dirt, the shit, the Heaven ... the collapse of opposites. You know, anthropologists of religion invented the word ‘liminal’, which was the space of ritual where you would do peyote and dance around the fire, wear costumes and dress up as an animal. That’s the first use of ‘liminal’; as a shamanistic term… the possibility of entering this mythological ‘heaven-space’.

SC: I’d like to circle back around to the practice of animation itself… you were talking about pedagogy, and what you referred to as the “media archaeologies” in traditional animation and media art.

CH: Well, there’s a “media archaeology” strain of animation, which has to do with looking back to precursors of simulations technology. You were talking about zoetropes, the early technologies that got skipped over when the culture went all-photo. I was also talking to you about a couple animators in my department who do hand drawn animation. I love their work, they deal with issues of the grotesque, they reject contemporary technology out of hand, they take an outsider artist position. Their work is emotionally powerful, very much dealing with issues of the body, of psychology … which in fact my work also does, issues of consciousness, of the ‘real’. What's interesting is we all admire each other's work very much but we fight like cats and dogs about pedagogy. They're always insisting I teach a character animation course, but I say “Over my dead body, you have no respect for my position!” <laughter> So we have these two feuding sectors within our Film, Video, and Animation department at SAIC. You have to understand, I'm an animation hire, but I say “I am not an animator!” and it’s not like we have any trouble filling either of these classes.

SC: In a way, this is an old argument. Do you think that this rejecting approach to technology, that reactionary attitude, might actually be a way around the problems, rather than to go right through it, by engaging it as we are doing?

CH: I don't think so. I think there is this idea of embracing an old-fashioned idea of authenticity. You reject the ‘Now’, which was the approach of the pre-Raphaelites.That was what was happening during the emergence of the first epoch of technology. When industrialization took command, you had this movement who wanted to go back to the medieval period. I actually love pre-Raphaelite painting – and I love the animations of my friends – but I do not think it's the solution. I don't think we can put on ostrich feathers and stick our heads in the sand. You see that: going off the grid. Disengage. But in fact, no! I don't want to capitulate to Donald Trump. I will NOT allow him to own Real-Fakeness. I will take Real-Fakeness and I will make it a cause for growth, affirmation and generative positivity ... goddamn you Trump, you will NOT own it!

SC: Ha! THAT is where I’m ending this interview, right there, okay? That’s IT.